Schema is the technical term for play urges. You know, those times when you ask a young child to stop jumping on the couch, they look you in the eye, but the urge to jump is so great that they keep on jumping…they just can’t help themselves.

Or maybe you have gone for a walk and a child was so engrossed in posting sticks down the drain that your suggestion to keep moving feels as if it has fallen on deaf ears…for the tenth time.

WHAT ARE SCHEMA?

Schema or play urges are often described as repeated patterns of behaviour. By repeating actions over and over, just like with the examples above, children are gathering information of that particular play urge, to store in their brain.

Remember, when a child is born they don’t have any prior experience of these play urges. It’s all new. So, they repeat these behaviours which in turn form categories of information in their brains.

Having exposure to a wide variety of experiences enables children to organise and interpret information quicker as there is prior knowledge available in the brain to draw from.

Originally Fredrick Bartlett a psychologist, laid the foundations in 1932 for what was to become schema theory. Jean Piaget built on this theory in his book The Origins of Intelligence in Children 1952. Richard Anderson then used schema theory in educational settings in the 1970s, specifically to do with literacy and it has evolved since then.

We often hear early childhood educators talking about children’s schema as a way to understand what the child is developing and what resources might support their schema.

WHY SCHEMAS ARE IMPORTANT?

Schema is how we organise and process the vast amounts of information that enter our brains. They enable us to take shortcuts by categorising this information.

Schema is the foundation of our brains memory. By following these urges children are making neural pathways in their brains to help their learning and development. This in turn improves the health of the brain and supports mental processes and brain function (Louis 2013).

They enable children to extend their thinking and knowledge of the world around them.

The more we know about schema, the more we understand that our children’s play patterns are a sign of brain development.

Schema also links well to the concept of child-led play, because when children are leading their play, there will be a schema in there somewhere.

HOW DO WE SUPPORT CHILDREN’S SCHEMA?

What I have found is that the more teachers and parents can understand and recognise what these schema or urges are, the better supported, deeper and more complex the child’s play is.

When we know schema signifies brain development saying ‘stop doing that’ gets switched into ‘keep doing that’ or ‘do that over there’.

Here are some concepts to consider when observing schema in children’s play:

- Leave them to it – they know what to do as it comes from deep within. They will ask if they need something so observation and curiosity about their schema are best

- Redirect it – if there is a safety concern or potential for damage, this is the time to step in and pause the play.

- Suggest alternatives – if you have needed to redirect them for safety, brainstorm or share some other ways to play in that way e.g. while we don’t want you to jump on the couch as the springs might break, you can jump off the steps or on the trampoline.

- Provide resources – ensure that your space has a variety of resources that cater to as many of the schema as possible. These can be naturally present or by adding resources that support schema play. It’s good to remember that during children’s play, the educator role can be fetching resources at their request!

For example, do you sometimes find stones, leaves, twigs, nuts, etc inside children’s pockets? Or is your car a stick nursery? (Gotta love that term!) Gathering and collecting are one of the urges that children love to follow. Having small bags or containers available in play environments or when going out for a walk can be a wonderful resource that supports children’s schema.

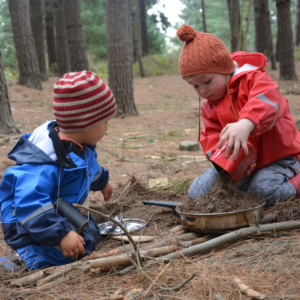

Another way to support children’s schema is to take it outside.

In outdoor nature play, there are many opportunities for schema to play out. Nature provides so many natural ingredients and elements that support children’s play, with open-ended resources and the freedom of space.

When you begin to understand more about schema, you will notice how nature is an amazing resource for all of your schema needs.

IS SCHEMA JUST FOR ECE?

I get asked this a lot. The thing to remember is that schema exists for everyone at any age. All information is categorised in our brains. It just looks different as children get older.

When we talk about schema in early education, we are coming from a place where a child has no prior knowledge on which to base their experiences. In these early years, schema are often action based and forms the foundation of all future schema that gets developed.

As children age their schema becomes more developed as they gather more and more information and store it in their brains. They will likely have preferences of schema, and for primary-aged children, their schema will become more complex as they continue to practice and repeat them.

For example, an older child who is focused on jumping might extend from jumping on and off things to jumping their bike or scooter or jumping over things that have a potential for harm.

Their knowledge and capacity are more advanced, hence their play is more advanced too.

It is also worth noting that children don’t suddenly stop wanting to play in the sandpit, the mud kitchen, or making huts with their friends. Taking these away when they reach a certain age is not helping our children. It is hindering them.

SCHEMA

Here is a list of 20 Schema with a brief description and the ways the schema could be played out. It includes ideas for resources that support each schema. There are both indoor and outdoor, natural and manmade resource lists to help give you ideas.

- Enclosure – getting inside something such as huts, boxes, shelters, bags, washing baskets, putting eggs in cartons, making pens for animals, wrapping acorns in leaves.

- Gathering/collecting – gathering items of interest or starting a collection e.g: pebbles, stones, shells, sticks, pinecones and leaves. Sometimes there is ‘giving & taking’ involved ie: giving a stone, and then taking it back. Having bags, baskets and bowls support this schema well.

- Transporting – carrying what you have collected to another place or moving something from one place to another. They could use a trolley, wheelbarrow, basket, bag, bowl, their own hands, their pocket, a bucket, or a pushchair.

- Deconstruction – taking something apart, knocking it down, or wrecking it. This could be done with stones, tee pee huts, piles of leaves, sand, mud, and sticks.

- Construction – building, putting something together, or constructing a model. This could be done using clay, sand, dirt, sticks, stones, branches, cones, leaves, nuts, pine needles, plywood, nails, planks of wood, tarpaulins, blankets, sheets, or pallets.

- Enveloping / Covering / Burying – making something disappear or putting an item under something else e.g. using leaves, soil, sand, sticks, stones, sheets, linen, bedding and paper. They could also use a spade for partial burials.

- Families – creating families with people or other items that represent families e.g. people, dolls, stones, sticks, animals, pillows, flax, leaves, wood, pebbles, nuts, seeds.

- Posting – putting something into a space or hole develops spatial intelligence e.g. balls into a box, acorns into a tree, holes in the ground, paper in a slot, clothes in a basket, or pipe cleaners in a colander, cups or cylinder. Other resources that could be used are blocks, toy animals, lego – anything they find actually!

- Trajectory – throwing an item or dropping something, either planned or unplanned. This might include balls, stones, sticks, sand, dirt, leaves, cones, acorns, softballs, bull’s eye, or themselves (climbing up and jumping). Perspex by the sandpit can also be useful for throwing sand against.

- Climbing – leaving the ground using hands and feet to pull themselves up. This could be done with small platforms, steppingstones, logs, stumps, or for crawlers – cushions, pillows, low platforms, planks, mounds of dirt, using furniture and items that are stable.

- Jumping – using legs to bend down and push off the ground into the air. Have safe landing areas where children can test their abilities and extend themselves. Using logs, planks, stumps, steps, branches, tires, and wooden cable reels.

- Wrestling – tumbling, playing on the ground in close body contact with one or more people. This is helping them understand their bodies in relation to others and consent.

- Running and Chasing – moving legs fast where both feet end up off the ground. Running after another person to catch them. As with children, some animals play chase just for fun.

- Tug of War – the act of pulling on something while one or more people pull on the other end. This involves learning to stand their ground using personal power which is critical for wellbeing.

- Transforming – the art of changing something in form, nature or appearance e.g. combining water, soil, sand, stones, leaves, or flour/water/salt/yeast to make bread, bread to toast, wool into socks.

- Orientation – the act of looking at things from a different body perspective e.g. a baby lying, rolling, tummy time, sitting. A child lying face up, on their back, their side, hanging, over the shoulder, up high, dangling, crawling backward. This can evolve into an intellectual mental attribute.

- Rotating – the act of turning around either an object or a person e.g. spinning in a circle on polished floors, spinning on a swing, rolling down a hill. Spinning grows brain connections and it can alter the way we feel (meditative).

- Balancing – establishing a relationship to gravity by oneself or with an object. Babies get a strong core by kicking and rolling. It is essential to crawl, walk, run, jump, hop, skip, climb, balance on edges and hop over stones. It works well with objects like blocks, stones, planks, a slackline and boxes.

- Patterning – arranging things in patterns, making patterns. The play unfolds the patterns of intelligence. This might include decorating a sandcastle or sorting, organising and classifying items by colour, shape, size, kind and number.

- Element play – playing with water, earth, air and fire. This includes the urge to poke a stick in a fire, but could also be done by creating a fire in a drum, or lighting a camping stove or BBQ. Water – watering plants, hoses, water pump, water wall, cleaning, dishes, sink, puddles, creating shallow stoney water courses. Earth – mud pits, gardening, sandpit, body painting. Air – swings, jungle gym, trees, hills, kites, planes.

SUMMARY

Having a variety of loose parts for children to play with helps them develop and strengthen their schema and make sense of the world. It helps them to organise all the information in their brain so they can access it in the future.

When we know about these schemas it becomes much easier for us to set up children’s play environments to best meet their developmental needs.

Providing a variety of loose parts in play environments will ensure that children can play in ways that their bodies have instinctively and intuitively known since the day they were born.

Let their internal compass guide them in developing their schema the best way they know how, through play.

REFLECTIVE QUESTIONS

To finish, I want to allow you to reflect and step back, observe, wonder, and get curious about how children play.

- When a child is playing, rather than looking at what they are playing with, ask yourself what is the pattern in their behaviour?

- What are they repeating?

- What is that deeper urge they are displaying?

- What are some of the schemas that I engaged with as a child?

- What schema is still significant to me in my life today?

- If an environment is resourced well, what is my role in children’s play?

- What additional resources could be available to help develop their play?

Sources and Further Reading:

Article: Schema in Children’s Play, by Clare Caro, http://www.nature-play.co.uk/blog/schemas-in-childrens-play

Article: Flying Start, Schema resource document edited by Sally Featherstone, http://www.flyingstart.uk.com/wp-content/uploads/2014/08/Schema.pdf

Article: A Complete Guide to Schema Theory and its Role in Education, by Beckton Loveless, https://www.educationcorner.com/schema-theory/

Article: How Children Learn through Schema, By Ann Mead and Lauren Ryan, https://static1.squarespace.com/static/56a6a6addc5cb4e8ec6d6d86/t/5c858576ee6eb059ac490e7c/1552254350453/how-children-learn-through-schemas.pdf

Book: The Sacred Urge to Play by Penelope Brownlee

Book: The Origins of Children’s Intelligence, by Jean Piaget, https://sites.pitt.edu/~strauss/origins_r.pdf

Book: Free to Learn, by Peter Gray Book: Balanced and Barefoot, by Angela Hanscom

Book: Last Child in the Woods, Saving our children from nature deficit disorder, by Richard Louv

Book: How to Raise a Wild Child, by Scott D Sampson

Book: Understanding Schemas in Young Children: Again! Again!, by Stella Louis